Consciousness considered in light of Ray Kurzweil’s Pattern Recognition Theory of Mind

This is an essay reviewing Ray Kurzweil’s How To Create a Mind. I completed this essay for UT Austin’s Computational Brain course (CS378) taught by Dana Ballard spring 2013. I earned recognition for many of my essays in this course during Ballard’s pen ceremonies, and went on to work in Ballard’s Embodied Cognition/VR Lab at UT Austin during the summer of 2013.

Consciousness considered in light of Ray Kurzweil’s Pattern Recognition Theory of Mind

Ray Kurzweil is a futurist and a reductionist. His Pattern Recognition Theory of Mind (PRTM) describes the fundamental unit of the neocortex as a pattern recognizer that computes and relays hierarchical information. By the physical wiring of pattern recognizers to one another, Kurzweil states that a mind is created with increasing linkage correlating to higher levels of abstraction in thinking and perception. His theory of the mind reduces consciousness to a physical system, thus one he believes can be rebuilt. However, applying computation to create a hypothesized consciousness crosses the bounds of science into the realm of philosophy. Issues arise over existence of the soul and acceptance of such technology as equivalent to its naturally occurring biological form. Either way, Kurzweil successfully applies his Pattern Recognition Theory of Mind’s computational axioms in a manner supported by modern neuroscience to construct a theory of mind that he believes could one day offer mankind infinite lifespans. If he is right the potentially enhanced person of the future will be exponentially different from the modern human being.

Gödel’s incompleteness theorems

Gödel’s incompleteness theorems state that every system will reduce to fundamental truths, or axioms, that are improvable within the system and disable it from exhibiting its own consistency. This means that in mathematics, “1 + 1” cannot be accepted to be “2” without applying two axioms. First, a numerical quantity “1” must be assumed to exist. Second, someone must be able to perform the computational action of “addition”. The incompleteness theorems hold that even after assuming “1” and “addition” exist, one cannot prove their existence through application of the mathematical system containing these entities. Thus, Kurzweil’s scientific depiction of the mind begins by establishing axioms that must be accepted in order to continue the application of his theory. He identifies the most reduced unit of his theory to be a pattern recognizer, a block of neural tissue that has a set behavior acting to compute an output signal after receiving input. These pattern recognizers are repeated throughout the neocortex, aligning with American neuroscientist Vernon Mountcastle’s hypothesis that the neocortex consists of a single repetitive component. Mountcastle proposed this repeating unit to be the cortical column, but modern research has shown repeating units to exist within the cortical columns themselves [Kurzweil 36]. These pattern recognizers therefore constitute Kurzweil’s first axiom in his theory. The repetitive units are interwoven within the cortical columns, and their connectivity to other pattern recognizers is a reflection of their function in the communication of thoughts. Completing this logic, Kurzweil’s second axiom is that these units must be able to communicate with each other. This is realized in the biological brain as physical connections between the dendrites of neurons, which are known to conduct signals with magnitude information. Therefore, Kurzweil’s PRTM assumes that pattern recognizers must exist and that these recognizers can create connections with other pattern recognizers. These assumptions are supported by modern research and understanding in neuroscience.

Categorical learning

The unit issue of the mind stems from the Hebbian learning model. This model is well known for introducing the maxim “cells that fire together wire together.” The model was introduced by Donald Hebb in his book The Organization of Behavior, and assumes the neuron to be the smallest assembly to adapt to new connections and strengthen or weaken them based cellular activity [2]. Hebb’s central assumption of the cell as the basic unit of learning is incorrect under Kurzweil. In his PRTM an assembly of about one hundred neurons learn by creation of connections with other groups of neurons, applying the Hebbian learning mechanic but not just applying it to a single neuron. It can therefore be concluded that Kurzweil rejects the idea of a Halle Berry cell. His interpretation of Quiroga et al’s findings in their paper “Invariant visual representation by single neurons in the human brain” [3] would be that they were measuring a neuron performing within the context of its pattern recognizer. Under his PRTM, this cell could simply be described as part of the pattern recognition sequence holding the concept of Halle Berry. The reason this cell also fired to a textual written version of her name is that the cell’s pattern recognizer is a part of a higher conceptualization of Halle Berry. Therefore, Kurzweil’s theory holds in the context of this neuroscience experiment that drew information from functioning biological brains. The existence of pattern recognition units is also supported by research conducted by Henry Markram, who searched for the smallest unit of the cortex that could act as a Hebbian assembly to support research for his Blue Brain Project ‘s simulation of the entire brain. He describes finding “elusive assemblies [whose] connectivity and synaptic weights are highly predictable and constrained” within the human brains [Kurzweil 80]. He hypothesized that these assemblies act as “Lego block” pieces in the construction of the incredibly complex mind. Markram originally guessed his “Lego blocks” to be the neocortex’s cortical columns structures, but held intuition that these have the possibility of containing sub-blocks. With the advantage of modern research, Kurzweil gladly refines Markram’s original hypothesis to describe each block as a group of neurons within the cortical column acting as a pattern recognition unit. In this way, each pattern recognizer under his PRTM possesses the ability to compute a behavioral response to its input, allowing different recognizer blocks to combine to create the experience of percepts. In light of the paper “A Continuous Semantic Space Describes the Representation of Thousands of Object and Action Categories across the Human Brain,” which demonstrates that the brain discriminates between objects by processing them through different physical maps in the brain [4], Kurzweil’s depiction of pattern recognizers piecing themselves together into a structured thought receives vast support. The published research team found it curious that certain categorical objects were not identified as having a localized point of response in the brain. Instead, their research demonstrated continuous semantic spaces to hold processing maps that elicited responses to several related categories. Kurzweil’s theory readily reasons with this phenomenon. Of course, similar objects run through similar pattern recognizers in the brain. And indeed, the mapping between pattern recognizers does not need to be constrained to a single focal point. Thus a categorical object is not understood in the mind within a physical chunk of the brain, but instead it elicits a range of pattern recognizers whose spread throughout the brain is continuous and dependent on the locations of the utilized pattern recognizers.

LISP

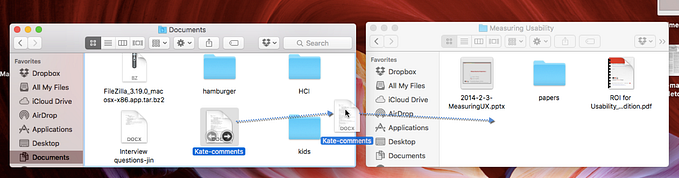

An experience is recalled as a sequence of events, or a one-dimensional list of actions. This is intuitive since humans remember things in the order they happened. Kurzweil claims that input to a pattern recognizer is one-dimensional as well. The items of the lists represent outputted magnitudes of relevant patterns in the cortical hierarchy, with the ordering depicting a remembered sequence of modules the memory passed through in the creation of its experience. In order to fill these one-dimensional lists, pattern information must be reduced from its original form into one that can be definitively named. In the PRTM, this is depicted as an evoked pattern recognizer adding its magnitude of stimulation to a recallable list. When consciously evoked, this list runs from the top down the program that codes the experience of a concept. Kurzweil finds the reduction of a stimulated neural firing pattern to a magnitude quantity analogous to the mathematical practice of vector quantization, where a large number of vectors is reduced to a smaller number of cluster points. These points compress information into namable entities whose identities can then be identified and communicated. In a similar way, the mind compresses information in order to relay this information through the established pattern recognizers in the mind. To the computer scientist, Kurzweil’s explanation of thinking seems programmable. Indeed, the commonly misunderstood (as outdated) programming language of LISP captures the functionality, pattern recognition, and recursive elements of the PRTM’s pattern recognizer. Kurzweil explains that “each pattern in the neocortex can be regarded as a LISP statement –each one constitutes a list of elements and each element can be another list” [Kurzweil 153].

Higher-level experiences

Kurzweil describes the neocortex of the mammalian brain as a biological system designed to understand hierarchical patterns. A message, directed by a list, relays through layers of consciousness to create the experiences of sensory perception, recognition, movement, spatial orientation reasoning, and rational thought. Connections pass the message between levels of pattern recognizers whose degree of interconnectivity determines the abstract nature of the message being conducted. This organization allows for the lowest conceptual level, sense perception, to create higher-level experiences. For example, light pattern input is received by the photoreceptive cells in the eye to relay useful information about the visual experience the owner of the eyeballs. However, the sensory information is initially rudimentary and must be strung through the conscious wiring of the viewer to create the final perceived image. Therefore, pattern information becomes confabulated by the mind in the creation of a conscious experience or thought. In humans, this confabulation has lead to the experience of higher-level concepts such as humor, metaphoric meaning, and love. These concepts do not exist apart from the mind, instead they depict the use of the outermost and therefore most abstract layers of the neocortex. In religions such as Hinduism, these higher abilities are personified in god and goddess forms to depict their transcendental nature. The Hindu goddess Saraswati, for example, anthropomorphized the expression of science, arts, and music –which are all higher-level human abilities. In order to establish higher-level connections, a human must believe in their possibility of existence and practice their elicitation. In spiritual terms, this could be realized as having faith in a higher power*. In terms of the PRTM, transcendental experiences promoted by religious beliefs can be supported by amazing rationality and simplicity. Kurzweil could describe such phenomena by claiming they draw on the outermost, and therefore highest, categorical levels of human understanding and represent huge amounts of pattern recognizers uniting together to provide an ultimate truth or understanding. Cultivation of such unity in mental action is the goal of yoga, which seeks to unite the practitioner with the absolute truth or Divine through focus and the re-dedication (to higher purposes) of the lower-level pattern recognizers attached to the material world.

I think –therefore I am

Kurzweil claims that application of his PRTM’s mechanics holds the potential to create a form of consciousness. Currently, no one believes their cell phone or computer is conscious and would not consider themselves a murderer if they happened to drop and break such merchandise. However, as computational systems become more and more like humans a conceptual muddle is created within the gray-areas surrounding the definition of consciousness. Kurzweil refers to the capacities of self-reflection and metacognition as parameters for determining consciousness, but states that the definition of consciousness cannot be scientifically ascertained because it is essentially a philosophical question. Philosophy holds many views on consciousness, but the ability of an individual to have a subjective experience is a commonly upheld baseline. Rene Descartes embodied this principle with “I think –therefore I am.” Descartes was a 17th century French philosopher who tried to scientifically prove the existence of anything without assuming any preconceived axioms, only to find that he could not prove the existence of anything (as further proof of the incompleteness theorems). Ultimately, Descartes realized he could only conclude the existence of one thing –himself, the person attempting to prove anything. This, in its essence, depicts subjective experience. Descartes could conclude that his mind elicited a thought to create his conscious experience and this proves his existence. Kurzweil contends that the “qualia,” or subjective experiences of an individual imply that a mind acts with a brain to create a unique conscious. Under this logic, cell phones and supercomputers of the future that can reason their own existence will be conscious and will be considered to have minds of their own. When Data was to be pulled apart on Star Trek: The Next Generation, his belief in his existence lead him and others to fight for his ‘life’.

A supercomputer of human knowledge could be considered more conscious than an individual human being

Assuming the existence of consciousness, the true depiction of consciousness is still debatable. One school of thought, dualism, claims that mind and consciousness are completely separate and hold different forms. Under this theory, material bodies hold spiritual souls that are composed of a different substance that may or may not interact with the material world. Dualistic theory implies that machines implementing Kurzweil’s PRTM will never achieve consciousness unless the spiritual element necessary for consciousness is somehow injected into the mechanical parts. This view thereby holds that technological devices will never be able to recreate or replace the essential soul essence located in the material brain that enables it to have subjective experience and be truly conscious. Another theory is panprotopsychism, which views all physical systems with the capacity for action as conscious. Under this theory, a rock that lacks any systematic abilities within itself is practically unconscious. However, a light switch that turns an electrical system on and off is slightly conscious in its ability to influence the material world. This philosophical theory depicts the experience of physical systems in the real world accurately, but can be said to have an ominous air. In George Orwell’s Animal Farm, the animal community is devastated and exploited after one of the observed Seven Commandments of Animalism changes to read, “All animals are equal, but some animals are more equal than others” [5]. Regarding all physical systems to be conscious, yet recognizing that some are more conscious than others rings with the same tone and could be detrimental when applied to society. None-the-less, Kurzweil supports panprotopsychism and states, “consciousness is an emergent property of a complex physical system” [Kurzweil 203]. In his view, physical systems can achieve different levels of consciousness, such that a mechanically efficient colony of ants can be considered more conscious than an individual ant. Kurzweil’s ant example puts the effect of humans creating consciousness within infinitely resourceful computational devices into perspective: that one day a supercomputer of human knowledge could be considered more conscious than an individual human being. Such a machine has the potential to dominate the world, just as the pigs grew to dominate their animal farm, by exploiting the fact that it is “more conscious than others.”

The ultimate limit of biology

Kurzweil sees the ultimate application of recreating mental abilities with technology as overcoming the inherent limitations of being bound to a biological body. He brings up the phenomena of the natural turnover of cells that continuously takes place in the body, with cellular layers being shed and replaced continuously. In this light, bodies are not statically the same from day to day but instead are dynamically changing. Animals with typically long lifespans are known to do this more effectively, demonstrating that it is healthy for the material “self” to change while completely retaining its identity. Therefore, Kurzweil concludes, the natural process of gradual replacement can be optimized by upcoming technology to replace mortal biological parts with immortal devices that perform the same functions. He does not think the individual’s identity will be altered differently than what is already experienced in the natural turnover within the biological self. Instead, the conversion to a new technological form will enable the replaced biological systems to be copied, backed-up, and re-created if ever a problem were to arise. In essence, no one could lose their memories or mental functionality and no one could ever die by losing their conscious identity. With this sentiment, Kurzweil crosses the line from friendly scientist into setting the stage for the human race to play God. The implications of life not subject to biological mortality will change everything about the world, and could lead to its destruction in many ways. What if people like Hilter never saw their time come to an end? Without natural biological turnover, Mother Earth would not be able to support her children. And finally, can technology bear the weight of trusting it to emulate the current experience of an essentially spiritual personality capable of subjective experience? Under these considerations, it is highly possible that a mechanical device replacing the neural tissue will not fully capture an essential element required to remain human. A missing component in this regard may abstract one away from being truly human. If Kurzweil really thinks people should replace the neurons in their brain with devices, he is placing a huge gamble on the accuracy of his theory of mind or any other theory applied to this endeavor. It can be argued that a human being will never recreate humanities’ true essence, that reductionists like Ray Kurzweil can shrink an image down to its parts but when they re-expand the image they will find it to be fuzzy, pixelated, and dissatisfying in essence. Obviously, this is bad when applied to human lives and the future of the species.

The context of a disprovable theory

Kurzweil’s Pattern Recognition Theory of Mind first establishes that “1 + 1” can be justified to equal “2” by outlining essential axioms assumed in application of the theory. The first axiom describes the theory’s fundamental component of a pattern recognizer, which Kurzweil describes as one hundred or so cells within a cortical column of the neocortex. His second axiom is that wirings between such pattern recognition units create a hierarchical ability in thinking. Implemented behavior in a system runs as lists through patterns in a manner similar to the programming language LISP. The sequential elicitation of conceptual patterns is capable of creating subjective experience and is Kurzweil’s proposed model for describing the computational behavior of the neocortex. Kurzweil offers a beautifully articulate theory of mind that resonates deeply with the human experience and its causative mental functions. His model may prove to withstand the test of time for the next decade or two, but if it is ever utilized in the replacement of a human brain, these brain-replacement people will be putting their souls on the line in the context of a disprovable theory. Kurzweil’s Pattern Recognition Theory of Mind is mathematically solid and seemingly accurate even in the philosophical context, but it is uncertain whether its application would actually capture humanities’ transcendental nature.

*This “higher power” is not an oppressive authority figure. Though it is worth noting that higher power can potentially be about connection in the same way a computer is more powerful with access to the internet.

Works Cited

[Kurzweil page#] Kurzweil, Ray. How to Create a Mind: The Secret of Human Thought Revealed. 2012. Viking Penguin. Kindle Edition.

[2] Hebb, Donald. The Organization of Behavior. 1949.

[3] Quiroga et al. “Invariant visual representation by single neurons in the human brain.” June 2005. Nature.

[4] Huth et al. A Continuous Semantic Space Describes the Representation of Thousands of Object and Action Categories across the Human Brain. Dec 20, 2012. Neuron 76.

[5] Orwell, George. Animal Farm. 1945.